Supported Decision-Making: A Copernican Revolution

People have been helping others to make decisions for as long as time itself. So, what’s the big deal about supported decision-making? Isn’t it just about providing good decision support? And hasn’t that been happening for a long time?

Well yes and no! Assisting people to make choices and have control over their lives is something supporters of people with disability have been doing for a long time. Their unique understanding of decision makers has led to amazing, creative ways to provide information, test options and explore the consequences of decisions. I am certain good decision support was happening long before we had ever heard of supported decision-making.

However, for many people with disability this support has not been readily available.

Supported decision-making developed in Canada in the early 1990s in opposition to adult guardianship[1]. Back then, supported decision-making was considered a process by which a person could be supported to discover their values, interests and talents in order to determine their own life[2]. It enabled people to become self-determining by removing the barriers that prevented them exercising their right to make decisions and provided the support necessary to make decisions and communicate their choices[3].

It was based on a set of principles[4] that included ideas such as:

All people have the right to self-determination and the right to make decisions with the support, affection and assistance of family and friends of their choosing,

Everyone has a will and is capable of making choices,

A cornerstone of supported decision-making is the existence of a trusting relationship between a person giving support and a person receiving support, and

The law must not discriminate on the basis of perceptions of a person’s capacity or competence.

From the very beginning supported decision-making was a mechanism of obtaining equal legal rights for people with disabilities in the area of decision making.

The principles guiding supported decision-making challenged how people thought about autonomy and capacity by seeking legal recognition of the interdependent nature of decision making. Supported decision-making rejected the assessment of an individual’s competence (mental capacity) and instead asked whether the decision-making process had been competent.

Supported decision-making was introduced to the world at the drafting of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. In 2006, when United Nations delegates were talking about people with disability having a right to equality before the law supported decision-making was raised as a legal alternative to substituted decision-making.

Article 12 of the Convention (Equal Recognition before the Law) says that governments have an obligation to provide people with disability with the support they need to be able to exercise their legal capacity. In the same way a person with a physical disability may need a ramp to be able to access a building, a person with a cognitive disability may need support to be able to exercise their decision-making rights (legal capacity)[5].

When trying to grasp the significance of the change in thinking brought about by Article 12 of the Convention, I think a helpful illustration is the Copernican Revolution.

In 1514 Nicolaus Copernicus, a mathematician and astronomer, proposed a model that put the sun at the centre of the universe rather than the Earth. His model set the planets in rotation around the sun, and introduced the earth’s daily rotation on its axis. Copernicus’ work was so radical it sparked a revolution.

In the same way Copernicus turned thinking about the universe upside down, supported decision-making turns substituted decision-making on its head.

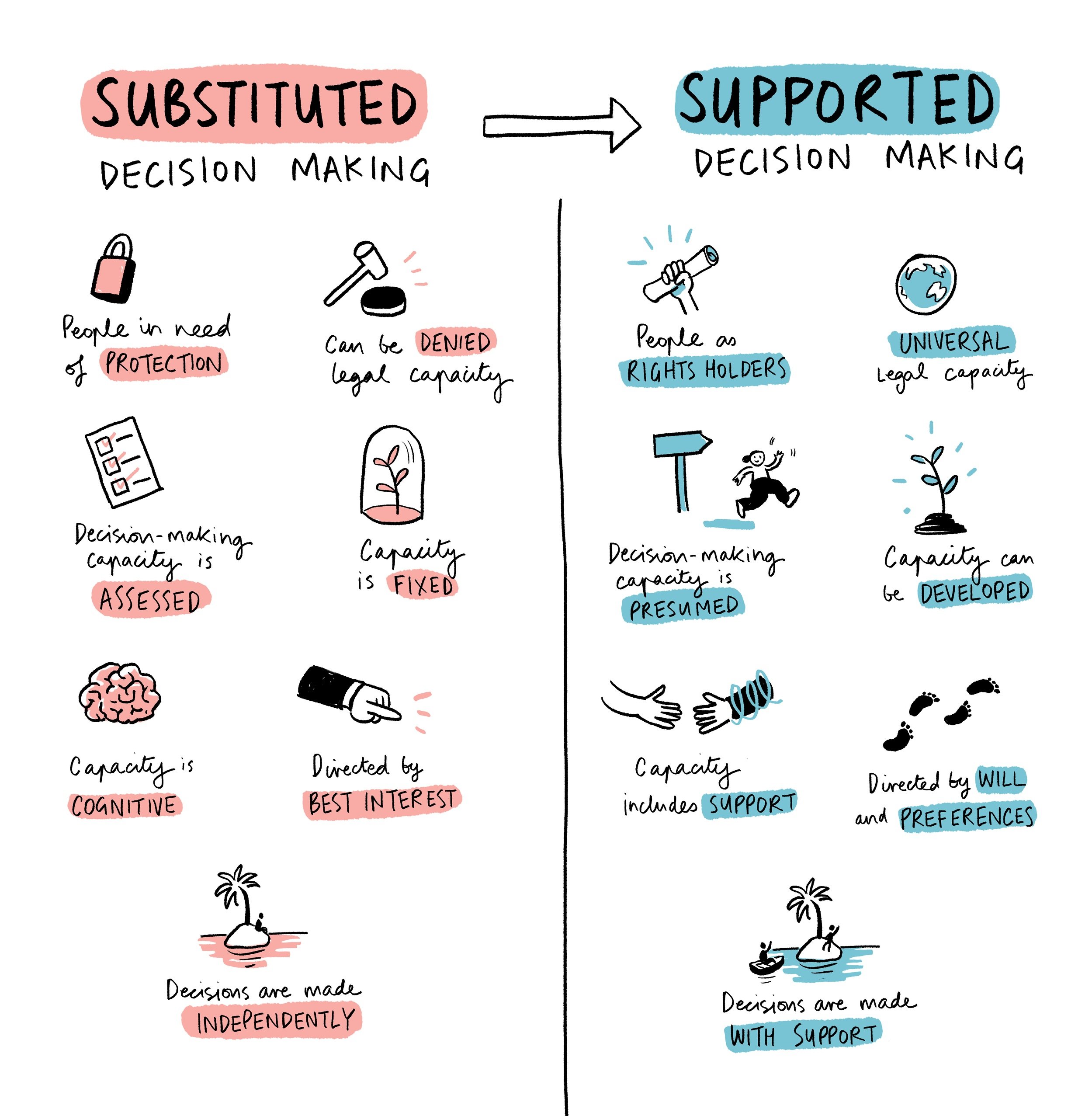

Rather than seeing people with disability as being in need of protection they are seen as rights holders.

People once denied their legal capacity are considered to have legal capacity universally.

Mental capacity assessments are no longer necessary because decision-making capacity is assumed.

Decision-making ability is not seen as fixed but is able to be developed.

Decision-making capacity is not thought about cognitively but includes the supports and accommodations available to the person in the decision-making process.

Where substituted decision-making was directed or guided by what was in the objective best interests of the person, supported decision-making is directed by the person’s will and preferences.

Decisions do not have to be made independently but can now be made with support.

Many people with disability have been subject to informal and formal substituted decision-making arrangements directed by what other people believe to be in their best interest. Article 12 of the Convention says this is no longer acceptable[6]. All people have a right to receive the support they need to direct the decisions which shape their lives and be legal decision makers.

So, while supported decision-making is about helping others to make decisions, its vision in many respects is revolutionary. Supported decision-making asks us to think about some fundamental things differently. By recognising decision making as an interdependent process and embracing a new way of thinking about decision-making capacity we are able to forge new ways for people with disability to take back control of their lives. Supported decision-making is asking us to change laws and social systems to become more inclusive, and I think that is something worth making a big deal about!

Illustrations by Jeffrey Phillips

[1] Gordon, R.M. (2000). The emergence of assisted (supported) decision-making in the Canadian law of adult guardianship and substitute decision-making. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 23(1), 61-77. doi:10.1016/S01602527(99)00034‐5

[2] Bodnar, F., & Coflin, J. (2003). Supported decision-making training manual. Saskatchewan Association for Community Living.

[3] Bach, M. (1998). Securing self-determination: Building the agenda in Canada. Retrieved from http://www.communitylivingbc.ca/what_we_do/innovation/pdf/Securing_the_Agenda_for_Self-Determination.pdf

[4] Canadian Association for Community Living [CACL] Task Force (1992). Report of the CACL Task Force on Alternatives to Guardianship. August, 1992. Retrieved from http://www.chrusp.org/media/AA/AG/chrusp-biz/.../CACLpaper.doc

[5] Salzman, L. (2010). Rethinking guardianship (again): Substituted decision-making as a violation of the integration mandate of title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act. Cardozo Legal Studies Research Paper No 282. University of Colorado Law Review, 81, 157-245. Retrieved from http://lawreview.colorado.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/10Salzman-FINAL_s.pdf

[6] Arstein-Kerslake, A. (2016). Legal capacity and supported decision-making: Respecting rights and empowering people. Melbourne Legal Studies Research Paper No. 736. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2818153